Tutorial Case Study: Consecutive IVF Pregnancies Following Fertility-Sparing Treatment in Endometrial Carcinoma

Case Summary

Patient: 25-year-old nulliparous female. Presented with irregular vaginal bleeding for 6 months. No prior fertility treatments or significant diseases.

Diagnostic workup confirmed grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma (EC), prompting fertility-sparing treatment due to her strong desire to preserve fertility.

The disease was presumed to be FIGO stage IA based on the absence of myometrial invasion on pelvic MRI and lack of extrauterine spread on imaging.

Initial Symptoms: Irregular bleeding. The disease was diagnosed by pelvic ultrasound showing a polyp, MRI revealed heterogeneous endometrial thickening with distinct demarcation between the endometrium and myometrium. . This was followed by hysteroscopy which showed an endometrial polyp of 4 mm in diameter, that was observed in the uterine cavity, along with uneven thickening of the endometrium and abnormally rich blood supply. The pathology examination showed atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a portion of highly differentiated endometrial carcinoma.

Clinical Course Timeline

The table below summarizes the patient’s clinical course.

Time point: Month 0

Event: Diagnosis

Intervention: Hysteroscopy, MRI

Outcome: Grade 1, stage IA EC confirmed

Time point: Month 1

Event: Hormonal Therapy

Intervention: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) + medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA)

Outcome: Treatment initiated

Time point: Months 3–12

Event: Monitoring

Intervention: Serial hysteroscopies every 3 months

Outcome: Remission with endometrial atrophy

Time point: Month 15

Event: IVF Cycle

Intervention: GnRH-a ultra-long protocol, ovarian stimulation

Outcome: 4 oocytes retrieved, 2 embryos transferred (fresh), 2 frozen

Time point: Month 24

Event: First Pregnancy

Intervention: Fresh embryo transfer (ET)

Outcome: Singleton live birth

Time point: Month 36

Event: Second Pregnancy

Intervention: Frozen embryo transfer (FET) after hormone replacement therapy

Outcome: Singleton live birth

Time point: Month 40

Event: Definitive Treatment

Intervention: Total hysterectomy, lymph node assessment

Outcome: No recurrence found

Comment on the Diagnostic procedure.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends that diagnosis must be confirmed with endometrial sampling, preferably by dilation and curettage (D&C), to ensure accurate histologic grading and to exclude higher-grade or non-endometrioid histology. Imaging, typically pelvic MRI, is advised to confirm the absence of myometrial invasion and extrauterine disease, as fertility-sparing therapy is only appropriate for strictly uterine-confined, noninvasive, grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma.

The NCCN also recommends consultation with a fertility specialist and genetic evaluation for inherited cancer risk. Patients must be counseled that fertility-sparing therapy is not the standard of care, and that definitive surgical management (TH/BSO and staging) is recommended after childbearing is complete, or if there is progression or lack of response to conservative therapy. All criteria outlined in the NCCN algorithm must be met before initiating fertility-sparing management, including the absence of metastatic disease and confirmation of noninvasive, grade 1 endometrioid histology by D&C (Abu-Rustum et al, 2023).

Table: NCCN Criteria for Fertility-Sparing Management in Young Patients with Endometrial Carcinoma

Criterion: Histologic Confirmation

Description: Biopsy-proven grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, preferably confirmed via dilation and curettage (D&C)

Criterion: Disease Stage

Description: Stage IA disease with no myometrial invasion (noninvasive)

Criterion: Metastatic Assessment

Description: No evidence of metastatic disease, including no extrauterine spread or nodal involvement

Criterion: Pregnancy Status

Description: Negative pregnancy test

Criterion: Medical Eligibility

Description: No contraindications to progestin therapy, such as a history of breast cancer, thromboembolic disease, or significant cardiovascular risk

Criterion: Patient Intent

Description: Desires fertility preservation and is willing to undergo close surveillance

Criterion: Multidisciplinary Evaluation

Description: Involves consultation with a fertility specialist and genetic evaluation for inherited cancer risk

Criterion: Informed Consent

Description: Patient has been counseled that fertility-sparing therapy is not the standard of care, and that definitive surgical treatment is recommended after childbearing, or in cases of progression or non-response

Note: This approach is not recommended for patients with high-grade tumors, non-endometrioid histologies, myometrial invasion, or metastatic disease (Abu-Rustum et al, 2023).

Clinical Decision Points

Fertility-Sparing Therapy

Decision: Initiate combined GnRH-a and MPA therapy.

Rationale: Suitable for grade 1, stage IA EC in patients desiring fertility, with a complete response rate of 50–77% (Abu-Rustum, 2023).

Pros: Preserves fertility, aligns with the patient’s reproductive goals.

Cons: ~35% recurrence risk, requires intensive monitoring every 3- 6 months via hysteroscopy or endometrial sampling.

Alternative: Immediate hysterectomy, which eliminates recurrence risk but precludes future pregnancies.

IVF Strategy

Decision: Use GnRH-a ultra-long protocol for ovarian stimulation, followed by fresh and frozen embryo transfers.

Rationale: Suppresses endometrial activity while maximizing pregnancy chances; Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) level of 1.75 ng/mL indicated suboptimal ovarian reserve (Park, 2024).

Pros: Higher live birth rate with assisted reproductive technology (ART) (39.4% vs. 14.9% spontaneous conception; ACOG, 2023), allows embryo cryopreservation for flexibility.

Cons: Risk of ovarian hyperstimulation, cost, and time-intensive process.

Alternative: Spontaneous conception, though less effective due to potential endometrial dysfunction post-therapy.

Delayed Definitive Treatment

Decision: Postpone hysterectomy until after the second pregnancy.

Rationale: No recurrence on regular monitoring, patient’s strong desire for a second child, informed consent, and multidisciplinary approval.

Pros: Achieved two live births, fulfilled the patient’s reproductive goals.

Cons: Risk of disease progression, psychological burden of ongoing cancer monitoring.

Alternative: Earlier surgery after the first pregnancy, reducing the risk of recurrence, but limiting family size.

Discussion Questions

This case exemplifies the rare but achievable outcome of consecutive successful pregnancies via ART following conservative management of endometrial cancer.

Fertility-Sparing Management in EC

Fertility-sparing management in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma is a viable option for those desiring to preserve fertility. The NCCN guidelines recommend continuous progestin-based therapy, which may include MPA or megestrol acetate (MA), for highly selected patients with grade 1, stage IA (noninvasive) disease (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023). GnRH agonists in combination with progestins, such as MPA, has also been explored and can be considered in specific cases (Tock et al. 2018).

The rationale for this approach is based on the relatively favorable prognosis of grade 1, stage IA EC and the desire to preserve fertility in young women. Progestin therapy has been shown to induce a complete response in approximately 50–77% of patients, with recurrence rates varying depending on the specific regimen used (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Park et al. 2015; Fan et al. 2018).

Monitoring during fertility-sparing treatment is crucial. The NCCN guidelines recommend close monitoring with endometrial sampling (biopsies or D&C) every 3 to 6 months to confirm response and detect any progression early (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023). This aligns with the practice of serial hysteroscopies every 3–6 months as mentioned in the question.

In summary, combined GnRH-a and MPA therapy is a suitable option for fertility-sparing management in patients with grade 1, stage IA EC, with serial hysteroscopies every 3–6 months recommended for monitoring response (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Tock et al. 2018).

What are the eligibility criteria for fertility-sparing treatment in endometrial cancer?

The eligibility criteria for fertility-sparing treatment in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma are well-defined and include several key factors:

- Histological Confirmation: The diagnosis must be confirmed as grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, preferably through D&C to ensure accurate grading and staging (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Stage of Disease: The carcinoma must be stage IA, which is confined to the endometrium without myometrial invasion (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021).

- Absence of High-Risk Features: There should be no evidence of myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, or metastatic disease. Patients with high-grade histologies such as serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, or carcinosarcoma are not eligible for fertility-sparing treatment (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021).

- Desire for Fertility Preservation: The patient must strongly desire to preserve fertility and be willing to undergo close monitoring and follow-up (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021).

- Negative Pregnancy Test: A negative pregnancy test is required before initiating fertility-sparing therapy to avoid potential teratogenic effects of the treatment (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Consultation with Specialists: It is recommended that patients consult with a fertility expert and undergo genetic evaluation of the tumor and assessment for inherited cancer risk (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Patient Counseling: Patients should be counseled that fertility-sparing therapy is not the standard of care for endometrial carcinoma and that definitive surgical treatment (hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) is recommended after childbearing is complete or if the conservative treatment fails (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

The NCCN guidelines provide a comprehensive framework for these criteria, emphasizing the importance of careful patient selection and rigorous follow-up (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

IVF Strategy

Option 1 (Use of a GnRH-a)

The literature supports the use of IVF following fertility-sparing treatment for grade 1, stage IA EC, particularly with the use of a GnRH-a ultra-long protocol followed by ovarian stimulation.

Protocol: A common approach in IVF involves using GnRH-a in an ultra-long protocol followed by ovarian stimulation. This protocol helps downregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, which can be beneficial in patients with EC who have undergone fertility-sparing treatment. Studies have shown this approach can lead to successful IVF outcomes in this patient population (Tock et al. 2018).

Option 2 (Use of a GnRH-antagonist)

The recommended ovarian stimulation protocol for IVF in patients with fertility-sparing EC (grade 1, stage 1A) typically involves the use of a GnRH-antagonist protocol. This approach is preferred due to its ability to minimize the duration of stimulation and reduce the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) (Purandare et al., 2025).

For patients with hormonally sensitive tumors, such as endometrial carcinoma, letrozole in combination with gonadotropins is recommended to reduce circulating estradiol levels during stimulation. This protocol helps mitigate the potential risk of tumor progression associated with elevated estrogen levels. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) supports the use of letrozole to maintain lower estradiol levels without compromising the number of oocytes or embryos retrieved (Purandare et al., 2014; Su et al., 2025).

The stimulation process generally involves the following steps:

- GnRH-Antagonist Protocol: Initiation of gonadotropins (FSH and/or LH) for ovarian stimulation, with the addition of a GnRH antagonist to prevent a premature luteinizing hormone (LH) surge.

- Letrozole: Administered concurrently with gonadotropins to suppress estradiol levels.

- Monitoring: Regular ultrasound and estradiol level assessments to monitor follicular development.

- Triggering Ovulation: Using a GnRH agonist or low-dose hCG to induce final oocyte maturation, minimizing the risk of OHSS.

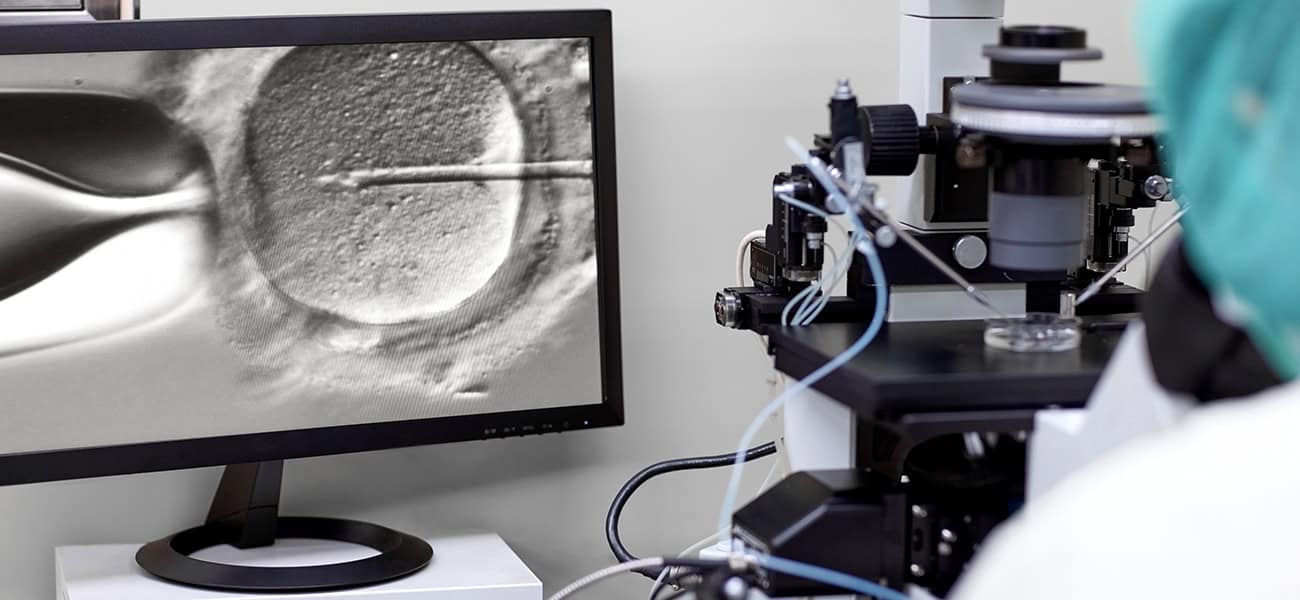

- Oocyte Retrieval: Performed transvaginally under ultrasound guidance.

This protocol ensures effective ovarian stimulation while minimizing the risk of exacerbating the underlying malignancy (Purandare et al., 2014).

Embryo Transfer:

First, the literature supports Fresh embryo transfer (ET) resulting in a successful pregnancy. A study by Kim et al. reports acceptable cumulative pregnancy rates after IVF in patients with early-stage endometrial carcinoma treated conservatively, with a clinical pregnancy rate per transfer of 26.5% and a live birth rate of 14.3% (Kim et al. 2019).

Second: Frozen embryo transfer (ET) after hormone replacement therapy, leading to a second live birth, is also supported. The same study indicated that multiple embryo transfer cycles, including frozen-thawed cycles, can result in successful pregnancies and live births (Kim et al. 2019).

Ovarian Reserve: An AMH level of 1.75 ng/mL indicates suboptimal ovarian reserve, a positive prognostic factor for successful IVF outcomes. The study by Park et al. demonstrated that patients with normal ovarian reserve, as indicated by AMH levels, had competent cumulative live birth rates through IVF procedures following fertility-preserving treatments (Park et al. 2024).

(Murdia et al. 2023)

Pregnancy outcome in this case: A poor ovarian response, potentially due to a combination of reduced ovarian reserve (evidenced by low AMH) and the use of an ultra-long protocol, may have resulted in profound ovarian suppression.

This case highlights (among others) the critical role of female age in determining oocyte quality and treatment outcomes. Achieving two live births from four oocytes is undoubtedly a favorable outcome.

In summary, the literature supports the use of a GnRH-a ultra-long protocol followed by ovarian stimulation, with both fresh and frozen embryo transfers leading to successful pregnancies and live births in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma who have undergone fertility-sparing treatment. This approach is feasible and effective, with careful monitoring and follow-up (Park et al. 2024).

How does ART improve pregnancy chances in this setting compared to spontaneous conception?

ART significantly improves pregnancy chances in patients with grade 1, stage IA EC who have undergone fertility-sparing treatment compared to spontaneous conception. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) notes that the live-birth rate in women using ART after fertility-sparing treatment is higher than that of women who attempt to achieve pregnancy spontaneously (39.4% vs. 14.9%; P = .001) (ACOG 2023). This is corroborated by a retrospective analysis showing that IVF and embryo transfer resulted in a 61.3% pregnancy rate and a 45.2% live birth rate in patients who achieved remission with MPA and metformin (ACOG 2023).

Additionally, a study by Friedlander et al. demonstrated that although the proportion of patients with a history of subfertility or infertility was high, the pregnancy outcomes were promising using ART, with a clinical pregnancy rate per transfer of 26.5% and a live birth rate of 14.3% (Friedlander et al. 2023). This indicates that ART can effectively overcome the fertility challenges posed by the underlying condition and its treatment.

In summary, ART improves pregnancy chances in this patient population by providing higher live birth rates compared to spontaneous conception, making it a valuable option for those desiring fertility after conservative management of early-stage EC (ACOG 2023; Friedlander et al. 2023).

Delayed Definitive Treatment

The decision to delay definitive surgery in a patient with grade 1, stage IA EC who has undergone fertility-sparing treatment can be supported by several key factors, including regular monitoring with no recurrence, the patient’s strong desire for a second child, informed consent, and multidisciplinary approval.

The NCCN guidelines recommend that fertility-sparing therapy can be considered for highly selected patients with grade 1, stage IA EC who wish to preserve fertility. The guidelines emphasize the importance of close monitoring with endometrial sampling (biopsies or D&C) every 3 to 6 months to confirm response and detect any progression early (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

A study by Gullo et al. supports the use of progestin-based therapy, such as MPA or MA, in the conservative management of early-stage EC, highlighting the importance of strict follow-up and psychological support for patients (Gullo et al. 2021).

In summary, delaying definitive surgery in a patient with grade 1, stage IA EC who has undergone fertility-sparing treatment is supported by regular monitoring with no recurrence, the patient’s strong desire for a second child, informed consent, and multidisciplinary approval, as recommended by the NCCN and supported by studies on fertility-sparing approaches and ART outcomes (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021; ACOG 2023).

What are the risks of delaying definitive surgical treatment in favor of fertility?

The risks of delaying definitive surgical treatment in favor of fertility preservation in a patient with grade 1, stage IA EC who has undergone fertility-sparing treatment include:

- Recurrence Risk: Despite regular monitoring, there is a significant risk of recurrence. The (NCCN guidelines report a recurrence rate of approximately 35% in patients who initially respond to progestin-based therapy (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Progression Risk: There is a potential for disease progression, which could lead to a more advanced stage of cancer that may be less responsive to treatment and could require more aggressive interventions (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Oncologic Outcomes: While fertility-sparing treatment can be effective, it is not the standard of care, and delaying definitive surgery may compromise long-term oncologic outcomes. The NCCN emphasizes that TH/BSO is recommended after childbearing is complete or if there is any evidence of disease progression (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Psychological Impact: The psychological burden of living with a cancer diagnosis and the uncertainty of recurrence can be significant. Gullo et al. highlight the importance of psychological support for patients undergoing fertility-sparing treatment (Gullo et al. 2021).

- Close Monitoring Requirements: The need for frequent and rigorous follow-up, including endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months, can be burdensome and stressful for patients (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Informed Consent and Multidisciplinary Approval: Patients must be fully informed about the risks and benefits of delaying definitive surgery. Multidisciplinary team approval ensures that the decision is made with comprehensive input from oncologists, fertility specialists, and other relevant healthcare providers (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021).

In summary, the risks of delaying definitive surgical treatment include recurrence, disease progression, potential compromise of oncologic outcomes, psychological impact, and the burden of close monitoring. These risks must be carefully weighed against the patient’s desire for fertility preservation, with informed consent and multidisciplinary team involvement being essential components of the decision-making process.

What strategies are employed to minimize cancer recurrence during fertility attempts?

To minimize cancer recurrence during fertility attempts in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma who have undergone fertility-sparing treatment, several strategies are employed:

- Continuous Progestin-Based Therapy: The NCCN recommends the use of continuous progestin-based therapy, such as MPA, MA, or a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD). This therapy helps maintain remission and prevent recurrence (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Close Monitoring: Regular monitoring with endometrial sampling (biopsies or D&C) every 3 to 6 months is crucial to detect any recurrence early. The NCCN guidelines emphasize the importance of this close follow-up (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Lifestyle Modifications: Counseling for weight management and lifestyle modifications is recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence. This includes maintaining a healthy weight and adopting a balanced diet (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Multidisciplinary Approach: A multidisciplinary team, including oncologists, fertility specialists, and genetic counselors, should be involved in the patient’s care to ensure comprehensive management and timely interventions if needed (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Prompt Pursuit of Pregnancy: Patients are advised to pursue pregnancy as soon as possible after achieving complete response. This minimizes the duration of exposure to potential recurrence risks while attempting to conceive (Gullo et al. 2021).

- Use of ART: ART, such as IVF, is often employed to maximize the chances of successful pregnancy while minimizing the time to conception. This approach has been shown to improve live birth rates compared to spontaneous conception (Gullo et al. 2021; ACOG 2023).

- Maintenance Therapy: For patients not attempting immediate conception, maintaining the LNG-IUD in situ can help prevent recurrence (Jang et al. 2024).

These strategies, grounded in the guidelines and literature, aim to balance the goals of fertility preservation and minimizing cancer recurrence.

A small prospective cohort study found that IVF after conservative fertility-sparing management in young patients with endometrial carcinoma was not associated with an increased risk of recurrence. This study prospectively followed 60 patients with atypical hyperplasia or grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma who underwent progestin-based fertility-sparing therapy, comparing recurrence rates between those who underwent IVF and those who did not. The study found no statistically significant increase in recurrence risk associated with IVF after remission (Vaugon et al. 2021).

Limitations and Evolving Considerations

While this case demonstrates a successful fertility-sparing approach followed by two IVF-assisted pregnancies in a patient with early-stage EC, several limitations must be acknowledged regarding the generalizability and applicability of this strategy:

Not all patients respond to progestin-based therapy. Reported complete response rates vary from 50% to 77%, and a significant proportion of patients may experience persistence or recurrent disease despite hormonal treatment. Furthermore, the recurrence risk remains substantial, with studies indicating rates as high as 35% in some cohorts, necessitating vigilant long-term surveillance (Wang et al. 2025; Giampaolino et al. 2022).

Clinical decision-making in such cases must be individualized. Factors such as patient age, ovarian reserve, comorbidities, tumor histology, and psychosocial context all influence the choice and timing of interventions. Multidisciplinary team involvement, including oncologists, fertility specialists, and genetic counselors, is crucial to optimizing outcomes and ensuring comprehensive care (Contreras et al. 2022; Centini et al. 2025).

Molecular classification has emerged as a valuable tool in predicting treatment response and recurrence risk. Patients with POLE mutations and p53 wild-type tumors tend to react better to progestin therapy, while those with mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd) and p53 abnormal (p53abn) tumors exhibit lower complete response rates and higher recurrence rates. This highlights the importance of personalized treatment plans based on molecular profiling (Wang et al. 2025; ACOG 2023).

Informed consent is essential, with patients being fully aware of the potential risks and benefits of delaying definitive surgery. Regular monitoring with endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months is recommended to detect any recurrence early and to guide timely interventions (Wang et al. 2025; Dellino et al. 2023).

In summary, while fertility-sparing treatment offers hope for young patients with early-stage EC, it requires careful patient selection, close monitoring, and a multidisciplinary approach to minimize risks and optimize outcomes.

Key Learning Points

- Fertility-sparing therapy is feasible and can be successful in select young patients with early-stage EC.

- IVF can significantly shorten time-to-pregnancy and allow flexibility via embryo cryopreservation.

- Close follow-up with hysteroscopic biopsies and hormonal suppression are essential to monitor remission and prevent recurrence.

- Surgical management should not be indefinitely delayed and should follow completed childbearing or upon any signs of disease return.

- This case highlights the rare yet possible outcome of two live births in a cancer survivor using ART post-fertility-preservation therapy.

Warning: Non-Standard Treatment and Exceptional Outcomes in Case Report

The case report on fertility-sparing treatment for a 25-year-old woman with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma, resulting in two successful IVF pregnancies, presents a non-standard approach and exceptional outcomes that may mislead readers. The initial use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) deviates from standard protocols, which typically involve oral progestins or a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), with GnRH-a reserved for specific cases. The reported success of two live births without recurrence is not typical, as literature indicates lower pregnancy rates and a 35% recurrence risk, potentially giving an overly optimistic view of fertility-sparing treatment.

Readers must exercise caution, as case reports are low-level evidence and not generalizable. The exceptional outcome and non-standard treatment should not be considered routine, and delaying definitive surgery carries significant oncologic risks. Consult current guidelines and healthcare providers to ensure evidence-based treatment plans, as this case may misrepresent typical practices and outcomes

Multiple-Choice Questions on IVF and Endometrial Carcinoma Case

Question 1: Eligibility for Fertility-Sparing Treatment

What is a key eligibility criterion for fertility-sparing treatment in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma?

- Histological confirmation of grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma

B. Presence of myometrial invasion on MRI

C. High-grade histology, such as serous carcinoma

D. No desire to preserve fertility

Correct Answer: A

Explanation: The document states that histological confirmation of grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, preferably through D&C, is a key eligibility criterion for fertility-sparing treatment (Abu-Rustum, 2023). Options B, C, and D are incorrect as they contradict the eligibility criteria, which exclude myometrial invasion, high-grade histologies, and lack of desire for fertility preservation.

Question 2: IVF Protocol Used

Which protocol was used for ovarian stimulation in the patient’s IVF cycle?

- Short GnRH antagonist protocol

B. GnRH-a ultra-long protocol

C. Natural cycle IVF

D. Mild stimulation protocol

Correct Answer: B

Explanation: The case specifies that the IVF cycle used a GnRH-a ultra-long protocol for ovarian stimulation, which suppresses endometrial activity while maximizing pregnancy chances (Park, 2024). Options A, C, and D are not mentioned in the case as the chosen protocol.

Question 3: Monitoring During Fertility-Sparing Treatment

How often is endometrial sampling recommended during fertility-sparing treatment to monitor response and detect recurrence?

- Every 1–2 months

B. Every 6–12 months

C. Every 3–6 months

D. Only at the start and end of treatment

Correct Answer: C

Explanation: The NCCN guidelines recommend close monitoring with endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months to confirm response and detect progression early (Abu-Rustum, 2023). Options A and B are incorrect as they do not align with the recommended frequency, and Option D is insufficient for ongoing monitoring.

Question 4: Risks of Delaying Definitive Treatment

What is a significant risk associated with delaying definitive surgical treatment in favor of fertility preservation?

- Guaranteed disease remission

B. Elimination of recurrence risk

C. Improved oncologic outcomes

D. Potential for disease progression

Correct Answer: D

Explanation: Delaying definitive surgery carries a risk of disease progression, which could lead to a more advanced stage of cancer (Abu-Rustum, 2023). Options A, B, and C are incorrect as fertility-sparing treatment does not guarantee remission, eliminate recurrence risk, or improve oncologic outcomes compared to definitive surgery.

Question 5: Advantages of ART Over Spontaneous Conception

Why does ART improve pregnancy chances compared to spontaneous conception in this patient population?

- Higher live birth rate

B. Lower cost and time commitment

C. Reduced need for hormonal therapy

D. Elimination of endometrial dysfunction

Correct Answer: A

Explanation: ART significantly improves pregnancy chances with a higher live birth rate (39.4% vs. 14.9% for spontaneous conception; ACOG, 2023). Options B, C, and D are incorrect as ART is costly and time-intensive, requires hormonal therapy, and does not eliminate endometrial dysfunction.

Question 6: Strategy to Minimize Cancer Recurrence

Which strategy is employed to minimize cancer recurrence during fertility attempts?

- Delaying pregnancy attempts indefinitely

B. Continuous progestin-based therapy

C. Avoiding lifestyle modifications

D. Reducing the frequency of endometrial sampling

Correct Answer: B

Explanation: Continuous progestin-based therapy, such as MPA, is recommended to maintain remission and prevent recurrence during fertility attempts (Abu-Rustum, 2023). Options A, C, and D are incorrect as they do not minimize recurrence; prompt pregnancy pursuit, lifestyle modifications, and frequent sampling are recommended.

References list

Abu-Rustum N, Yashar C, Arend R, et al. Uterine Neoplasms, Version 1.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(2):181–209. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2023.0006.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Management of Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia or Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia: ACOG Clinical Consensus No. 5. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142(3):735–744. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005297.

Centini G, Colombi I, Ianes I, et al. Fertility Sparing in Endometrial Cancer: Where Are We Now? Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(1):112. doi:10.3390/cancers17010112.

Contreras NA, Sabadell J, Verdaguer P, Julià C, Fernández-Montolí ME. Fertility-Sparing Approaches in Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia and Endometrial Cancer Patients: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2531. doi:10.3390/ijms23052531.

Dellino M, Cerbone M, Laganà AS, et al. Upgrading Treatment and Molecular Diagnosis in Endometrial Cancer—Driving New Tools for Endometrial Preservation? Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9780. doi:10.3390/ijms24119780.

Fan Z, Li H, Hu R, et al. Fertility-Preserving Treatment in Young Women With Grade 1 Presumed Stage IA Endometrial Adenocarcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28(2):385–393. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000001164.

Friedlander H, Blakemore JK, McCulloh DH, Fino ME. Fertility-Sparing Treatment and Assisted Reproductive Technology in Patients With Endometrial Carcinoma and Endometrial Hyperplasia: Pregnancy Outcomes After Embryo Transfer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(7):2123. doi:10.3390/cancers15072123.

Giampaolino P, Cafasso V, Boccia D, et al. Fertility-Sparing Approach in Patients With Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer Grade 2 Stage IA (FIGO): A Qualitative Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:4070368. doi:10.1155/2022/4070368.

Gullo G, Etrusco A, Cucinella G, et al. Fertility-Sparing Approach in Women Affected by Stage I and Low-Grade Endometrial Carcinoma: An Updated Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11825. doi:10.3390/ijms222111825.

Jang EB, Lee AJ, So KA, et al. Risk Factors for the Recurrence in Patients With Early Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer Achieving Complete Remission for Fertility-Sparing Hormonal Treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2024;191:19–24. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2024.09.015.

Kasum M, Šimunic V, Oreskovic S, Beketic-Oreskovic L. Fertility preservation with ovarian stimulation protocols prior to cancer treatment. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(3):182-186. doi:10.3109/09513590.2013.860123.

Kim MJ, Choe SA, Kim MK, et al. Outcomes of in Vitro Fertilization Cycles Following Fertility-Sparing Treatment in Stage IA Endometrial Cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300(4):975–980. doi:10.1007/s00404-019-05237-2.

Murdia K, Chandra V, Bhoi NR, et al. Age-related change in AMH in women seeking fertility – a hospital-based study across India. J IVF-Worldwide. 2023;1(1-3):1–13. doi:10.46989/001c.87500.

Park J, Yu EJ, Lee N, et al. The Analysis of in Vitro Fertilization Outcomes After Fertility-Preserving Therapy for Endometrial Hyperplasia or Carcinoma. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2024;89(6):461–468. doi:10.1159/000539315.

Park JY, Nam JH. Progestins in the Fertility-Sparing Treatment and Retreatment of Patients With Primary and Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. Oncologist. 2015;20(3):270–278. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0445.

Purandare NC, Ryan GA, El Helali A, Crosby D. Fertility stimulation protocols in women with cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025;169(3):876–878. doi:10.1002/ijgo.16170.

Su HI, Lacchetti C, Letourneau J, et al. Fertility preservation in people with cancer: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43(12):1488–1515. doi:10.1200/JCO.24.02782.

Tock S, Jadoul P, Squifflet JL, et al. Fertility Sparing Treatment in Patients With Early Stage Endometrial Cancer, Using a Combination of Surgery and GnRH Agonist: A Monocentric Retrospective Study and Review of the Literature. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:240. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00240.

Vaugon M, Peigné M, Phelippeau J, Gonthier C, Koskas M. IVF Impact on the Risk of Recurrence of Endometrial Adenocarcinoma After Fertility-Sparing Management. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;43(3):495–502. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.06.007.

Wang Y, Lai T, Chu D, et al. The Association of Molecular Classification With Fertility-Sparing Treatment of Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia and Endometrial Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1506639. doi:10.3389/fonc.2025.1506639.

Tutorial Case Study: Consecutive IVF Pregnancies Following Fertility-Sparing Treatment in Endometrial Carcinoma

Case Summary

Patient: 25-year-old nulliparous female. Presented with irregular vaginal bleeding for 6 months. No prior fertility treatments or significant diseases.

Diagnostic workup confirmed grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma (EC), prompting fertility-sparing treatment due to her strong desire to preserve fertility.

The disease was presumed to be FIGO stage IA based on the absence of myometrial invasion on pelvic MRI and lack of extrauterine spread on imaging.

Initial Symptoms: Irregular bleeding. The disease was diagnosed by pelvic ultrasound showing a polyp, MRI revealed heterogeneous endometrial thickening with distinct demarcation between the endometrium and myometrium. . This was followed by hysteroscopy which showed an endometrial polyp of 4 mm in diameter, that was observed in the uterine cavity, along with uneven thickening of the endometrium and abnormally rich blood supply. The pathology examination showed atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a portion of highly differentiated endometrial carcinoma.

Clinical Course Timeline

The table below summarizes the patient’s clinical course.

Time point: Month 0

Event: Diagnosis

Intervention: Hysteroscopy, MRI

Outcome: Grade 1, stage IA EC confirmed

Time point: Month 1

Event: Hormonal Therapy

Intervention: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) + medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA)

Outcome: Treatment initiated

Time point: Months 3–12

Event: Monitoring

Intervention: Serial hysteroscopies every 3 months

Outcome: Remission with endometrial atrophy

Time point: Month 15

Event: IVF Cycle

Intervention: GnRH-a ultra-long protocol, ovarian stimulation

Outcome: 4 oocytes retrieved, 2 embryos transferred (fresh), 2 frozen

Time point: Month 24

Event: First Pregnancy

Intervention: Fresh embryo transfer (ET)

Outcome: Singleton live birth

Time point: Month 36

Event: Second Pregnancy

Intervention: Frozen embryo transfer (FET) after hormone replacement therapy

Outcome: Singleton live birth

Time point: Month 40

Event: Definitive Treatment

Intervention: Total hysterectomy, lymph node assessment

Outcome: No recurrence found

Comment on the Diagnostic procedure.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends that diagnosis must be confirmed with endometrial sampling, preferably by dilation and curettage (D&C), to ensure accurate histologic grading and to exclude higher-grade or non-endometrioid histology. Imaging, typically pelvic MRI, is advised to confirm the absence of myometrial invasion and extrauterine disease, as fertility-sparing therapy is only appropriate for strictly uterine-confined, noninvasive, grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma.

The NCCN also recommends consultation with a fertility specialist and genetic evaluation for inherited cancer risk. Patients must be counseled that fertility-sparing therapy is not the standard of care, and that definitive surgical management (TH/BSO and staging) is recommended after childbearing is complete, or if there is progression or lack of response to conservative therapy. All criteria outlined in the NCCN algorithm must be met before initiating fertility-sparing management, including the absence of metastatic disease and confirmation of noninvasive, grade 1 endometrioid histology by D&C (Abu-Rustum et al, 2023).

Table: NCCN Criteria for Fertility-Sparing Management in Young Patients with Endometrial Carcinoma

Criterion: Histologic Confirmation

Description: Biopsy-proven grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, preferably confirmed via dilation and curettage (D&C)

Criterion: Disease Stage

Description: Stage IA disease with no myometrial invasion (noninvasive)

Criterion: Metastatic Assessment

Description: No evidence of metastatic disease, including no extrauterine spread or nodal involvement

Criterion: Pregnancy Status

Description: Negative pregnancy test

Criterion: Medical Eligibility

Description: No contraindications to progestin therapy, such as a history of breast cancer, thromboembolic disease, or significant cardiovascular risk

Criterion: Patient Intent

Description: Desires fertility preservation and is willing to undergo close surveillance

Criterion: Multidisciplinary Evaluation

Description: Involves consultation with a fertility specialist and genetic evaluation for inherited cancer risk

Criterion: Informed Consent

Description: Patient has been counseled that fertility-sparing therapy is not the standard of care, and that definitive surgical treatment is recommended after childbearing, or in cases of progression or non-response

Note: This approach is not recommended for patients with high-grade tumors, non-endometrioid histologies, myometrial invasion, or metastatic disease (Abu-Rustum et al, 2023).

Clinical Decision Points

Fertility-Sparing Therapy

Decision: Initiate combined GnRH-a and MPA therapy.

Rationale: Suitable for grade 1, stage IA EC in patients desiring fertility, with a complete response rate of 50–77% (Abu-Rustum, 2023).

Pros: Preserves fertility, aligns with the patient’s reproductive goals.

Cons: ~35% recurrence risk, requires intensive monitoring every 3- 6 months via hysteroscopy or endometrial sampling.

Alternative: Immediate hysterectomy, which eliminates recurrence risk but precludes future pregnancies.

IVF Strategy

Decision: Use GnRH-a ultra-long protocol for ovarian stimulation, followed by fresh and frozen embryo transfers.

Rationale: Suppresses endometrial activity while maximizing pregnancy chances; Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) level of 1.75 ng/mL indicated suboptimal ovarian reserve (Park, 2024).

Pros: Higher live birth rate with assisted reproductive technology (ART) (39.4% vs. 14.9% spontaneous conception; ACOG, 2023), allows embryo cryopreservation for flexibility.

Cons: Risk of ovarian hyperstimulation, cost, and time-intensive process.

Alternative: Spontaneous conception, though less effective due to potential endometrial dysfunction post-therapy.

Delayed Definitive Treatment

Decision: Postpone hysterectomy until after the second pregnancy.

Rationale: No recurrence on regular monitoring, patient’s strong desire for a second child, informed consent, and multidisciplinary approval.

Pros: Achieved two live births, fulfilled the patient’s reproductive goals.

Cons: Risk of disease progression, psychological burden of ongoing cancer monitoring.

Alternative: Earlier surgery after the first pregnancy, reducing the risk of recurrence, but limiting family size.

Discussion Questions

This case exemplifies the rare but achievable outcome of consecutive successful pregnancies via ART following conservative management of endometrial cancer.

Fertility-Sparing Management in EC

Fertility-sparing management in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma is a viable option for those desiring to preserve fertility. The NCCN guidelines recommend continuous progestin-based therapy, which may include MPA or megestrol acetate (MA), for highly selected patients with grade 1, stage IA (noninvasive) disease (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023). GnRH agonists in combination with progestins, such as MPA, has also been explored and can be considered in specific cases (Tock et al. 2018).

The rationale for this approach is based on the relatively favorable prognosis of grade 1, stage IA EC and the desire to preserve fertility in young women. Progestin therapy has been shown to induce a complete response in approximately 50–77% of patients, with recurrence rates varying depending on the specific regimen used (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Park et al. 2015; Fan et al. 2018).

Monitoring during fertility-sparing treatment is crucial. The NCCN guidelines recommend close monitoring with endometrial sampling (biopsies or D&C) every 3 to 6 months to confirm response and detect any progression early (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023). This aligns with the practice of serial hysteroscopies every 3–6 months as mentioned in the question.

In summary, combined GnRH-a and MPA therapy is a suitable option for fertility-sparing management in patients with grade 1, stage IA EC, with serial hysteroscopies every 3–6 months recommended for monitoring response (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Tock et al. 2018).

What are the eligibility criteria for fertility-sparing treatment in endometrial cancer?

The eligibility criteria for fertility-sparing treatment in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma are well-defined and include several key factors:

- Histological Confirmation: The diagnosis must be confirmed as grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, preferably through D&C to ensure accurate grading and staging (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Stage of Disease: The carcinoma must be stage IA, which is confined to the endometrium without myometrial invasion (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021).

- Absence of High-Risk Features: There should be no evidence of myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, or metastatic disease. Patients with high-grade histologies such as serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, or carcinosarcoma are not eligible for fertility-sparing treatment (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021).

- Desire for Fertility Preservation: The patient must strongly desire to preserve fertility and be willing to undergo close monitoring and follow-up (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021).

- Negative Pregnancy Test: A negative pregnancy test is required before initiating fertility-sparing therapy to avoid potential teratogenic effects of the treatment (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Consultation with Specialists: It is recommended that patients consult with a fertility expert and undergo genetic evaluation of the tumor and assessment for inherited cancer risk (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Patient Counseling: Patients should be counseled that fertility-sparing therapy is not the standard of care for endometrial carcinoma and that definitive surgical treatment (hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) is recommended after childbearing is complete or if the conservative treatment fails (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

The NCCN guidelines provide a comprehensive framework for these criteria, emphasizing the importance of careful patient selection and rigorous follow-up (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

IVF Strategy

Option 1 (Use of a GnRH-a)

The literature supports the use of IVF following fertility-sparing treatment for grade 1, stage IA EC, particularly with the use of a GnRH-a ultra-long protocol followed by ovarian stimulation.

Protocol: A common approach in IVF involves using GnRH-a in an ultra-long protocol followed by ovarian stimulation. This protocol helps downregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, which can be beneficial in patients with EC who have undergone fertility-sparing treatment. Studies have shown this approach can lead to successful IVF outcomes in this patient population (Tock et al. 2018).

Option 2 (Use of a GnRH-antagonist)

The recommended ovarian stimulation protocol for IVF in patients with fertility-sparing EC (grade 1, stage 1A) typically involves the use of a GnRH-antagonist protocol. This approach is preferred due to its ability to minimize the duration of stimulation and reduce the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) (Purandare et al., 2025).

For patients with hormonally sensitive tumors, such as endometrial carcinoma, letrozole in combination with gonadotropins is recommended to reduce circulating estradiol levels during stimulation. This protocol helps mitigate the potential risk of tumor progression associated with elevated estrogen levels. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) supports the use of letrozole to maintain lower estradiol levels without compromising the number of oocytes or embryos retrieved (Purandare et al., 2014; Su et al., 2025).

The stimulation process generally involves the following steps:

- GnRH-Antagonist Protocol: Initiation of gonadotropins (FSH and/or LH) for ovarian stimulation, with the addition of a GnRH antagonist to prevent a premature luteinizing hormone (LH) surge.

- Letrozole: Administered concurrently with gonadotropins to suppress estradiol levels.

- Monitoring: Regular ultrasound and estradiol level assessments to monitor follicular development.

- Triggering Ovulation: Using a GnRH agonist or low-dose hCG to induce final oocyte maturation, minimizing the risk of OHSS.

- Oocyte Retrieval: Performed transvaginally under ultrasound guidance.

This protocol ensures effective ovarian stimulation while minimizing the risk of exacerbating the underlying malignancy (Purandare et al., 2014).

Embryo Transfer:

First, the literature supports Fresh embryo transfer (ET) resulting in a successful pregnancy. A study by Kim et al. reports acceptable cumulative pregnancy rates after IVF in patients with early-stage endometrial carcinoma treated conservatively, with a clinical pregnancy rate per transfer of 26.5% and a live birth rate of 14.3% (Kim et al. 2019).

Second: Frozen embryo transfer (ET) after hormone replacement therapy, leading to a second live birth, is also supported. The same study indicated that multiple embryo transfer cycles, including frozen-thawed cycles, can result in successful pregnancies and live births (Kim et al. 2019).

Ovarian Reserve: An AMH level of 1.75 ng/mL indicates suboptimal ovarian reserve, a positive prognostic factor for successful IVF outcomes. The study by Park et al. demonstrated that patients with normal ovarian reserve, as indicated by AMH levels, had competent cumulative live birth rates through IVF procedures following fertility-preserving treatments (Park et al. 2024).

(Murdia et al. 2023)

Pregnancy outcome in this case: A poor ovarian response, potentially due to a combination of reduced ovarian reserve (evidenced by low AMH) and the use of an ultra-long protocol, may have resulted in profound ovarian suppression.

This case highlights (among others) the critical role of female age in determining oocyte quality and treatment outcomes. Achieving two live births from four oocytes is undoubtedly a favorable outcome.

In summary, the literature supports the use of a GnRH-a ultra-long protocol followed by ovarian stimulation, with both fresh and frozen embryo transfers leading to successful pregnancies and live births in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma who have undergone fertility-sparing treatment. This approach is feasible and effective, with careful monitoring and follow-up (Park et al. 2024).

How does ART improve pregnancy chances in this setting compared to spontaneous conception?

ART significantly improves pregnancy chances in patients with grade 1, stage IA EC who have undergone fertility-sparing treatment compared to spontaneous conception. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) notes that the live-birth rate in women using ART after fertility-sparing treatment is higher than that of women who attempt to achieve pregnancy spontaneously (39.4% vs. 14.9%; P = .001) (ACOG 2023). This is corroborated by a retrospective analysis showing that IVF and embryo transfer resulted in a 61.3% pregnancy rate and a 45.2% live birth rate in patients who achieved remission with MPA and metformin (ACOG 2023).

Additionally, a study by Friedlander et al. demonstrated that although the proportion of patients with a history of subfertility or infertility was high, the pregnancy outcomes were promising using ART, with a clinical pregnancy rate per transfer of 26.5% and a live birth rate of 14.3% (Friedlander et al. 2023). This indicates that ART can effectively overcome the fertility challenges posed by the underlying condition and its treatment.

In summary, ART improves pregnancy chances in this patient population by providing higher live birth rates compared to spontaneous conception, making it a valuable option for those desiring fertility after conservative management of early-stage EC (ACOG 2023; Friedlander et al. 2023).

Delayed Definitive Treatment

The decision to delay definitive surgery in a patient with grade 1, stage IA EC who has undergone fertility-sparing treatment can be supported by several key factors, including regular monitoring with no recurrence, the patient’s strong desire for a second child, informed consent, and multidisciplinary approval.

The NCCN guidelines recommend that fertility-sparing therapy can be considered for highly selected patients with grade 1, stage IA EC who wish to preserve fertility. The guidelines emphasize the importance of close monitoring with endometrial sampling (biopsies or D&C) every 3 to 6 months to confirm response and detect any progression early (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

A study by Gullo et al. supports the use of progestin-based therapy, such as MPA or MA, in the conservative management of early-stage EC, highlighting the importance of strict follow-up and psychological support for patients (Gullo et al. 2021).

In summary, delaying definitive surgery in a patient with grade 1, stage IA EC who has undergone fertility-sparing treatment is supported by regular monitoring with no recurrence, the patient’s strong desire for a second child, informed consent, and multidisciplinary approval, as recommended by the NCCN and supported by studies on fertility-sparing approaches and ART outcomes (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021; ACOG 2023).

What are the risks of delaying definitive surgical treatment in favor of fertility?

The risks of delaying definitive surgical treatment in favor of fertility preservation in a patient with grade 1, stage IA EC who has undergone fertility-sparing treatment include:

- Recurrence Risk: Despite regular monitoring, there is a significant risk of recurrence. The (NCCN guidelines report a recurrence rate of approximately 35% in patients who initially respond to progestin-based therapy (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Progression Risk: There is a potential for disease progression, which could lead to a more advanced stage of cancer that may be less responsive to treatment and could require more aggressive interventions (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Oncologic Outcomes: While fertility-sparing treatment can be effective, it is not the standard of care, and delaying definitive surgery may compromise long-term oncologic outcomes. The NCCN emphasizes that TH/BSO is recommended after childbearing is complete or if there is any evidence of disease progression (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Psychological Impact: The psychological burden of living with a cancer diagnosis and the uncertainty of recurrence can be significant. Gullo et al. highlight the importance of psychological support for patients undergoing fertility-sparing treatment (Gullo et al. 2021).

- Close Monitoring Requirements: The need for frequent and rigorous follow-up, including endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months, can be burdensome and stressful for patients (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Informed Consent and Multidisciplinary Approval: Patients must be fully informed about the risks and benefits of delaying definitive surgery. Multidisciplinary team approval ensures that the decision is made with comprehensive input from oncologists, fertility specialists, and other relevant healthcare providers (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023; Gullo et al. 2021).

In summary, the risks of delaying definitive surgical treatment include recurrence, disease progression, potential compromise of oncologic outcomes, psychological impact, and the burden of close monitoring. These risks must be carefully weighed against the patient’s desire for fertility preservation, with informed consent and multidisciplinary team involvement being essential components of the decision-making process.

What strategies are employed to minimize cancer recurrence during fertility attempts?

To minimize cancer recurrence during fertility attempts in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma who have undergone fertility-sparing treatment, several strategies are employed:

- Continuous Progestin-Based Therapy: The NCCN recommends the use of continuous progestin-based therapy, such as MPA, MA, or a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD). This therapy helps maintain remission and prevent recurrence (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Close Monitoring: Regular monitoring with endometrial sampling (biopsies or D&C) every 3 to 6 months is crucial to detect any recurrence early. The NCCN guidelines emphasize the importance of this close follow-up (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Lifestyle Modifications: Counseling for weight management and lifestyle modifications is recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence. This includes maintaining a healthy weight and adopting a balanced diet (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Multidisciplinary Approach: A multidisciplinary team, including oncologists, fertility specialists, and genetic counselors, should be involved in the patient’s care to ensure comprehensive management and timely interventions if needed (Abu-Rustum et al. 2023).

- Prompt Pursuit of Pregnancy: Patients are advised to pursue pregnancy as soon as possible after achieving complete response. This minimizes the duration of exposure to potential recurrence risks while attempting to conceive (Gullo et al. 2021).

- Use of ART: ART, such as IVF, is often employed to maximize the chances of successful pregnancy while minimizing the time to conception. This approach has been shown to improve live birth rates compared to spontaneous conception (Gullo et al. 2021; ACOG 2023).

- Maintenance Therapy: For patients not attempting immediate conception, maintaining the LNG-IUD in situ can help prevent recurrence (Jang et al. 2024).

These strategies, grounded in the guidelines and literature, aim to balance the goals of fertility preservation and minimizing cancer recurrence.

A small prospective cohort study found that IVF after conservative fertility-sparing management in young patients with endometrial carcinoma was not associated with an increased risk of recurrence. This study prospectively followed 60 patients with atypical hyperplasia or grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma who underwent progestin-based fertility-sparing therapy, comparing recurrence rates between those who underwent IVF and those who did not. The study found no statistically significant increase in recurrence risk associated with IVF after remission (Vaugon et al. 2021).

Limitations and Evolving Considerations

While this case demonstrates a successful fertility-sparing approach followed by two IVF-assisted pregnancies in a patient with early-stage EC, several limitations must be acknowledged regarding the generalizability and applicability of this strategy:

Not all patients respond to progestin-based therapy. Reported complete response rates vary from 50% to 77%, and a significant proportion of patients may experience persistence or recurrent disease despite hormonal treatment. Furthermore, the recurrence risk remains substantial, with studies indicating rates as high as 35% in some cohorts, necessitating vigilant long-term surveillance (Wang et al. 2025; Giampaolino et al. 2022).

Clinical decision-making in such cases must be individualized. Factors such as patient age, ovarian reserve, comorbidities, tumor histology, and psychosocial context all influence the choice and timing of interventions. Multidisciplinary team involvement, including oncologists, fertility specialists, and genetic counselors, is crucial to optimizing outcomes and ensuring comprehensive care (Contreras et al. 2022; Centini et al. 2025).

Molecular classification has emerged as a valuable tool in predicting treatment response and recurrence risk. Patients with POLE mutations and p53 wild-type tumors tend to react better to progestin therapy, while those with mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd) and p53 abnormal (p53abn) tumors exhibit lower complete response rates and higher recurrence rates. This highlights the importance of personalized treatment plans based on molecular profiling (Wang et al. 2025; ACOG 2023).

Informed consent is essential, with patients being fully aware of the potential risks and benefits of delaying definitive surgery. Regular monitoring with endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months is recommended to detect any recurrence early and to guide timely interventions (Wang et al. 2025; Dellino et al. 2023).

In summary, while fertility-sparing treatment offers hope for young patients with early-stage EC, it requires careful patient selection, close monitoring, and a multidisciplinary approach to minimize risks and optimize outcomes.

Key Learning Points

- Fertility-sparing therapy is feasible and can be successful in select young patients with early-stage EC.

- IVF can significantly shorten time-to-pregnancy and allow flexibility via embryo cryopreservation.

- Close follow-up with hysteroscopic biopsies and hormonal suppression are essential to monitor remission and prevent recurrence.

- Surgical management should not be indefinitely delayed and should follow completed childbearing or upon any signs of disease return.

- This case highlights the rare yet possible outcome of two live births in a cancer survivor using ART post-fertility-preservation therapy.

Warning: Non-Standard Treatment and Exceptional Outcomes in Case Report

The case report on fertility-sparing treatment for a 25-year-old woman with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma, resulting in two successful IVF pregnancies, presents a non-standard approach and exceptional outcomes that may mislead readers. The initial use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) deviates from standard protocols, which typically involve oral progestins or a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), with GnRH-a reserved for specific cases. The reported success of two live births without recurrence is not typical, as literature indicates lower pregnancy rates and a 35% recurrence risk, potentially giving an overly optimistic view of fertility-sparing treatment.

Readers must exercise caution, as case reports are low-level evidence and not generalizable. The exceptional outcome and non-standard treatment should not be considered routine, and delaying definitive surgery carries significant oncologic risks. Consult current guidelines and healthcare providers to ensure evidence-based treatment plans, as this case may misrepresent typical practices and outcomes

Multiple-Choice Questions on IVF and Endometrial Carcinoma Case

Question 1: Eligibility for Fertility-Sparing Treatment

What is a key eligibility criterion for fertility-sparing treatment in patients with grade 1, stage IA endometrial carcinoma?

- Histological confirmation of grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma

B. Presence of myometrial invasion on MRI

C. High-grade histology, such as serous carcinoma

D. No desire to preserve fertility

Correct Answer: A

Explanation: The document states that histological confirmation of grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, preferably through D&C, is a key eligibility criterion for fertility-sparing treatment (Abu-Rustum, 2023). Options B, C, and D are incorrect as they contradict the eligibility criteria, which exclude myometrial invasion, high-grade histologies, and lack of desire for fertility preservation.

Question 2: IVF Protocol Used

Which protocol was used for ovarian stimulation in the patient’s IVF cycle?

- Short GnRH antagonist protocol

B. GnRH-a ultra-long protocol

C. Natural cycle IVF

D. Mild stimulation protocol

Correct Answer: B

Explanation: The case specifies that the IVF cycle used a GnRH-a ultra-long protocol for ovarian stimulation, which suppresses endometrial activity while maximizing pregnancy chances (Park, 2024). Options A, C, and D are not mentioned in the case as the chosen protocol.

Question 3: Monitoring During Fertility-Sparing Treatment

How often is endometrial sampling recommended during fertility-sparing treatment to monitor response and detect recurrence?

- Every 1–2 months

B. Every 6–12 months

C. Every 3–6 months

D. Only at the start and end of treatment

Correct Answer: C

Explanation: The NCCN guidelines recommend close monitoring with endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months to confirm response and detect progression early (Abu-Rustum, 2023). Options A and B are incorrect as they do not align with the recommended frequency, and Option D is insufficient for ongoing monitoring.

Question 4: Risks of Delaying Definitive Treatment

What is a significant risk associated with delaying definitive surgical treatment in favor of fertility preservation?

- Guaranteed disease remission

B. Elimination of recurrence risk

C. Improved oncologic outcomes

D. Potential for disease progression

Correct Answer: D

Explanation: Delaying definitive surgery carries a risk of disease progression, which could lead to a more advanced stage of cancer (Abu-Rustum, 2023). Options A, B, and C are incorrect as fertility-sparing treatment does not guarantee remission, eliminate recurrence risk, or improve oncologic outcomes compared to definitive surgery.

Question 5: Advantages of ART Over Spontaneous Conception

Why does ART improve pregnancy chances compared to spontaneous conception in this patient population?

- Higher live birth rate

B. Lower cost and time commitment

C. Reduced need for hormonal therapy

D. Elimination of endometrial dysfunction

Correct Answer: A

Explanation: ART significantly improves pregnancy chances with a higher live birth rate (39.4% vs. 14.9% for spontaneous conception; ACOG, 2023). Options B, C, and D are incorrect as ART is costly and time-intensive, requires hormonal therapy, and does not eliminate endometrial dysfunction.

Question 6: Strategy to Minimize Cancer Recurrence

Which strategy is employed to minimize cancer recurrence during fertility attempts?

- Delaying pregnancy attempts indefinitely

B. Continuous progestin-based therapy

C. Avoiding lifestyle modifications

D. Reducing the frequency of endometrial sampling

Correct Answer: B

Explanation: Continuous progestin-based therapy, such as MPA, is recommended to maintain remission and prevent recurrence during fertility attempts (Abu-Rustum, 2023). Options A, C, and D are incorrect as they do not minimize recurrence; prompt pregnancy pursuit, lifestyle modifications, and frequent sampling are recommended.

References list

Abu-Rustum N, Yashar C, Arend R, et al. Uterine Neoplasms, Version 1.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(2):181–209. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2023.0006.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Management of Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia or Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia: ACOG Clinical Consensus No. 5. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142(3):735–744. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005297.

Centini G, Colombi I, Ianes I, et al. Fertility Sparing in Endometrial Cancer: Where Are We Now? Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(1):112. doi:10.3390/cancers17010112.

Contreras NA, Sabadell J, Verdaguer P, Julià C, Fernández-Montolí ME. Fertility-Sparing Approaches in Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia and Endometrial Cancer Patients: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2531. doi:10.3390/ijms23052531.

Dellino M, Cerbone M, Laganà AS, et al. Upgrading Treatment and Molecular Diagnosis in Endometrial Cancer—Driving New Tools for Endometrial Preservation? Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9780. doi:10.3390/ijms24119780.

Fan Z, Li H, Hu R, et al. Fertility-Preserving Treatment in Young Women With Grade 1 Presumed Stage IA Endometrial Adenocarcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28(2):385–393. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000001164.

Friedlander H, Blakemore JK, McCulloh DH, Fino ME. Fertility-Sparing Treatment and Assisted Reproductive Technology in Patients With Endometrial Carcinoma and Endometrial Hyperplasia: Pregnancy Outcomes After Embryo Transfer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(7):2123. doi:10.3390/cancers15072123.

Giampaolino P, Cafasso V, Boccia D, et al. Fertility-Sparing Approach in Patients With Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer Grade 2 Stage IA (FIGO): A Qualitative Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:4070368. doi:10.1155/2022/4070368.

Gullo G, Etrusco A, Cucinella G, et al. Fertility-Sparing Approach in Women Affected by Stage I and Low-Grade Endometrial Carcinoma: An Updated Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11825. doi:10.3390/ijms222111825.

Jang EB, Lee AJ, So KA, et al. Risk Factors for the Recurrence in Patients With Early Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer Achieving Complete Remission for Fertility-Sparing Hormonal Treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2024;191:19–24. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2024.09.015.

Kasum M, Šimunic V, Oreskovic S, Beketic-Oreskovic L. Fertility preservation with ovarian stimulation protocols prior to cancer treatment. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(3):182-186. doi:10.3109/09513590.2013.860123.

Kim MJ, Choe SA, Kim MK, et al. Outcomes of in Vitro Fertilization Cycles Following Fertility-Sparing Treatment in Stage IA Endometrial Cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300(4):975–980. doi:10.1007/s00404-019-05237-2.

Murdia K, Chandra V, Bhoi NR, et al. Age-related change in AMH in women seeking fertility – a hospital-based study across India. J IVF-Worldwide. 2023;1(1-3):1–13. doi:10.46989/001c.87500.

Park J, Yu EJ, Lee N, et al. The Analysis of in Vitro Fertilization Outcomes After Fertility-Preserving Therapy for Endometrial Hyperplasia or Carcinoma. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2024;89(6):461–468. doi:10.1159/000539315.

Park JY, Nam JH. Progestins in the Fertility-Sparing Treatment and Retreatment of Patients With Primary and Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. Oncologist. 2015;20(3):270–278. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0445.

Purandare NC, Ryan GA, El Helali A, Crosby D. Fertility stimulation protocols in women with cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025;169(3):876–878. doi:10.1002/ijgo.16170.

Su HI, Lacchetti C, Letourneau J, et al. Fertility preservation in people with cancer: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43(12):1488–1515. doi:10.1200/JCO.24.02782.

Tock S, Jadoul P, Squifflet JL, et al. Fertility Sparing Treatment in Patients With Early Stage Endometrial Cancer, Using a Combination of Surgery and GnRH Agonist: A Monocentric Retrospective Study and Review of the Literature. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:240. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00240.

Vaugon M, Peigné M, Phelippeau J, Gonthier C, Koskas M. IVF Impact on the Risk of Recurrence of Endometrial Adenocarcinoma After Fertility-Sparing Management. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;43(3):495–502. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.06.007.

Wang Y, Lai T, Chu D, et al. The Association of Molecular Classification With Fertility-Sparing Treatment of Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia and Endometrial Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1506639. doi:10.3389/fonc.2025.1506639.

biweekly insights